Streams and Pipes

Overview

Programs can send their output to (and receive their input from) another program or another file.

If you combine multiple commands this way, you can write little programs in your shell that work on lines of text.

These lines of text are typically filtered, pattern-matched, transformed and then printed or sent as input into yet another program.

If your lines of text are separated by a common delimiter character - like spaces, tabs, commas - then shell commands can understand this and treat the data as a list of records of tabular data.

I/O Streams

I think the term “stream” is a pretty good way to describe the concept. Data flows from in from one direction and it can be split, combined, or diverted in various ways with a little bit of plumbing.

On a Unix-based system (that includes Mac/Darwin and Linux), the kernel treats any data source or device the same way it treats a normal file. This just means that there is a consistent interface for reading, seeking, opening, closing, writing to all of these data sources.

The reason I bring this up is because it will help you understand what streams are if you think of them as files. Files that don’t actually exist anywhere on disk and disappear when the command sequence is complete.

Multiple programs can keep a file open and read/write to it at the same time. One program can read the contents of a file and, when it gets to the end, wait a while and then check to see if more data has been added to the end of the file by another program.

STDIN

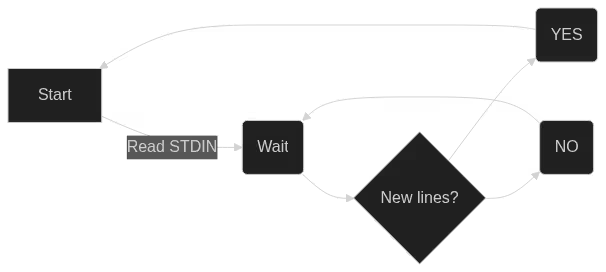

When a program reads from STDIN (“standard input”) stream, it will read any information in that stream and then wait for more data to be written. When it detects new data, it will process that, then wait again (until it receives a special “end of file” sequence).

In your interactive shell, STDIN defaults to the characters you type from your keyboard, like editing a file in a text editor. But, usually, we write another command to produce specific output and “pipe” that to the next program, to become that program’s STDIN stream. This is like writing a program to produce a very specific input “file” for the next program to read.

STDOUT

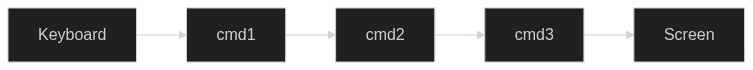

You may have guessed by now, STDOUT is an output stream, and it goes to your monitor by default. The output of a program is written to this “file” and, if we “pipe” it to another command, this program’s STDOUT is also the next program’s STDIN. We can combine programs this way into chains or “pipelines” to do complex tasks.

The first input starts with my keyboard, then the output of each command becomes the input of each subsequent command, and then the last output stream goes to my monitor for display.

STDERR

The other important stream to know is STDERR, which is the “error” output stream. This is typically where error or warning text is printed by a program.

This stream also goes to your monitor, so it will look like it’s part of the STDOUT data. But they are actually two different streams and you can point them off in different directions.

# "2" is the ID or "file descriptor" for STDERR

rm /tmp/this-file-does-not-exist 2>/dev/null

The example above would try to remove the file and, if the file didn’t exist or there was some problem, would send the error output to the “null device” (basically send it to nowhere). The STDOUT would still go to the screen, but the STDERR would not be printed.

Redirection

You can “redirect” STDOUT to another destination, like a file or another output stream. You can also “redirect” input to STDIN from another source, besides your keyboard.

You can redirect output to a file on disk.

# create or overwrite /tmp/hi.txt

echo "HI" > /tmp/hi.txt

# append to existing /tmp/hi.txt

echo "HELLO" >> /tmp/hi.txt

A single “>” will send the output to the file /tmp/hi.txt, creating the file if it does not exist, or overwriting it if it does exist.

Using “>>” will append the output to the existing file, instead of overwriting it.

If you redirect an output stream to /dev/null, it will suppress that output. You might do this, for example, if you want to run a command that might fail and you don’t want the STDERR output if it does.

ls ~/tmp /doesnotexist

# ls: cannot access '/doesnotexist': No such file or directory

# ~/tmp:

# file1

# file2

# ...

ls ~/tmp /doesnotexist 2>/dev/null

# ~/tmp:

# file1

# file2

# ...

You can redirect the output from one stream to another output stream as well. You might want to do this if you want to treat STDERR like part of STDIN, so you can filter for errors or regular output with one command.

# this time, the error message is on STDOUT so grep can match it

ls ~/tmp /doesnotexist 2>&1 | grep 'No such file'

# ls: cannot access '/doesnotexist': No such file or directory

You can also redirect output to the default STDIN and another program can read that:

cat ~/tmp/hi.txt

# HI

# HELLO

# sed reads from STDIN

sed 's/HI/HELLO/' <(cat ~/tmp/hi.txt)

# HELLO

# HELLO

# you can redirect input AND output

sed 's/HI/HELLO/' <(cat ~/tmp/hi.txt) > ~/tmp/hello.txt

tee

When you redirect your output to a file, you don’t see it on your screen. If you want to see the output on your screen AND redirect it to a file, use the tee command.

tail -f /var/log/nginx/access.log | grep mypage.html | tee /tmp/mypage.log

In this example, we’re “tailing” a log file - watching it for changes and printing them to the screen as soon as something new is written to the file.

The grep command filters the live log output, so that it only prints lines that mention mypage.html.

Then tee will redirect the output to the specified file, /tmp/mypage.log, while also printing it to your screen (STDOUT).

Pipes

With pipes, you directly connect two programs at opposite ends of a shared data stream. One program is the producer, which writes it’s output directly to the stream. The other program is the consumer, which reads it’s input directly from the stream.

If you’ve read the other sections in this module, you’ve already seen plenty of examples of this concept in other examples.

Use | to pipe to programs together. The first program (left of |) will write to its output stream, and the second program will read that same stream as its input stream. As the first program writes more lines of data, the second program will process it and pass through to its own output stream.

# - find all markdown files under the current directory

# - filter for files that start with '_' (output from find has leading "./")

# - for each filename, run wc-l to show number of lines

# - sort, in reverse order, so longest files are on top

find . -name '*.md' | grep -E '^./_' | xargs wc -l | sort -r

Normally, only the STDOUT of a program gets piped to the next one. If you want to send STDERR along with it, you can use "|&" to combine both output streams into one.

Try it Out

Let’s write a command by building it up incrementally, and examining the output at each stage.

First, navigate to the top-level directory of this repository. If you haven’t already cloned the repository, use the following command:

git clone https://github.com/dczmer/davelab

Let’s find all the markdown files in this project, sort them by how many lines long they are, the export that as JSON.

First, find all the metadata files:

find . -name '*.md'

# README.md

# about.md

# index.md

# ...

Then we use xargs to run a command over every line from the previous command’s output. Each line is a filename that we will pass to wc -l to count the number of lines in that file.

find . -name '*.md' | xargs wc -l

# 17 ./README.md

# 42 ./about.md

# 7 ./index.md

# ...

# 2828 total

Notice the “total” line at the bottom. We want to remove that. We can use head, which normally gives you the first few lines of a stream, with a count value of -1 which will effectively just truncate the very last line.

Use “\” to break a command over multiple lines.

find . -name '*.md' \

| xargs wc -l \

| head -n-1

# 17 ./README.md

# 42 ./about.md

# 7 ./index.md

# ...

Now sort that list, numerically (-n), in descending order (-r “reverse”).

find . -name '*.md' \

| xargs wc -l \

| head -n-1 \

| sort -nr

# 461 ./_using_the_shell/04_commands.md

# 342 ./_using_the_shell/02_expansion-signals.md

# 339 ./_zsh_configuration/02_prompt.md

# ...

Then we can use column --json to export it as JSON.

find . -name '*.md' \

| xargs wc -l \

| head -n-1 \

| sort -nr \

| column --table-columns=size,name --json

# {

# "table": [

# {

# "size": "461",

# "name": "./_using_the_shell/04_commands.md"

# },{

# "size": "342",

# "name": "./_using_the_shell/02_expansion-signals.md"

# },{

If it’s too much to read at once, you can pipe it to less:

find . -name '*.md' \

| xargs wc -l \

| head -n-1 \

| sort -nr \

| column --table-columns=size,name --json \

| less